Chinese calligraphy, a gem in the world’s artistic treasury, has evolved over three millennia through the medium of Chinese characters. It embodies not only the transformation of writing systems but also the integration of aesthetic sensibilities and philosophical thought, standing as a testament to the profound wisdom of Chinese civilization.

I. Origins of Calligraphic Art (Pre-Qin Period)

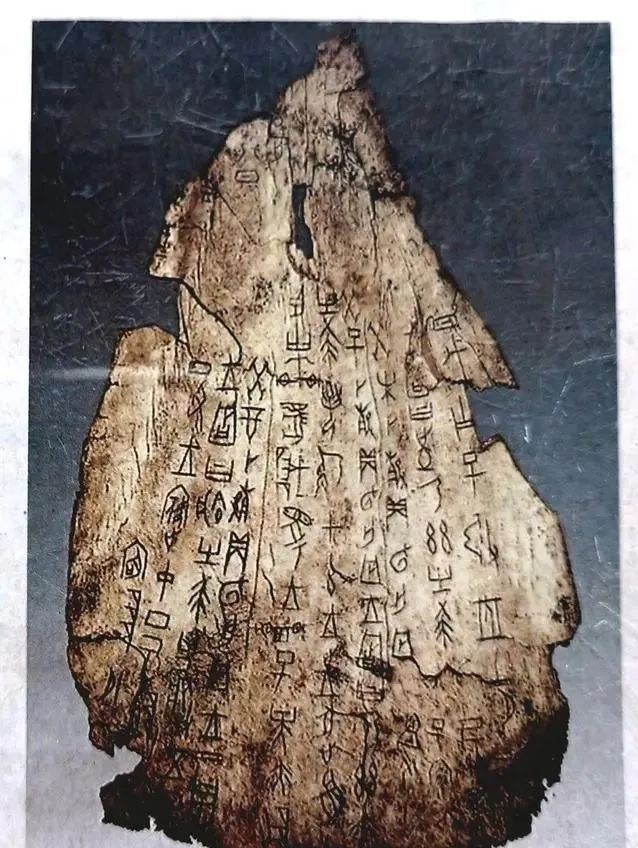

Oracle Bone Script (Late Shang Dynasty)

Inscriptions incised on tortoise shells and animal bones (c. 14th–11th century BCE) mark the dawn of Chinese calligraphy. These angular, vigorous lines combined practical record-keeping with ritualistic ornamentation.

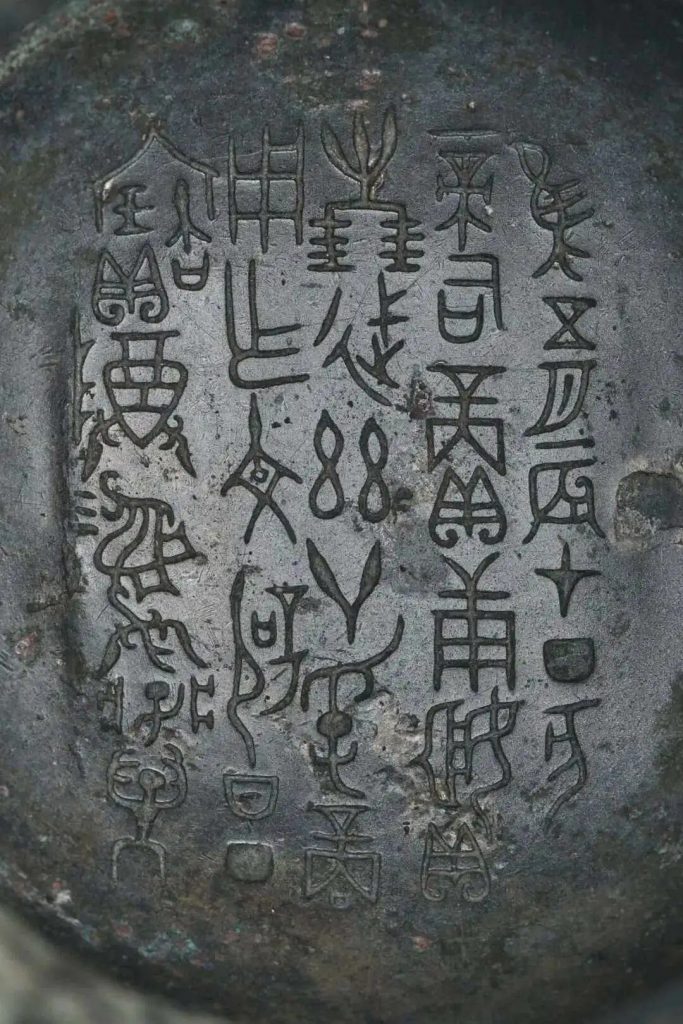

Bronze Inscriptions (Western Zhou Dynasty)

Cast onto ritual bronzes (e.g., Da Yu Ding and Mao Gong Ding), these scripts feature robust, rounded strokes and majestic structures. Their formalization laid the groundwork for Qin’s Small Seal script.

II. The Golden Age of Script Evolution (Qin-Han to Wei-Jin)

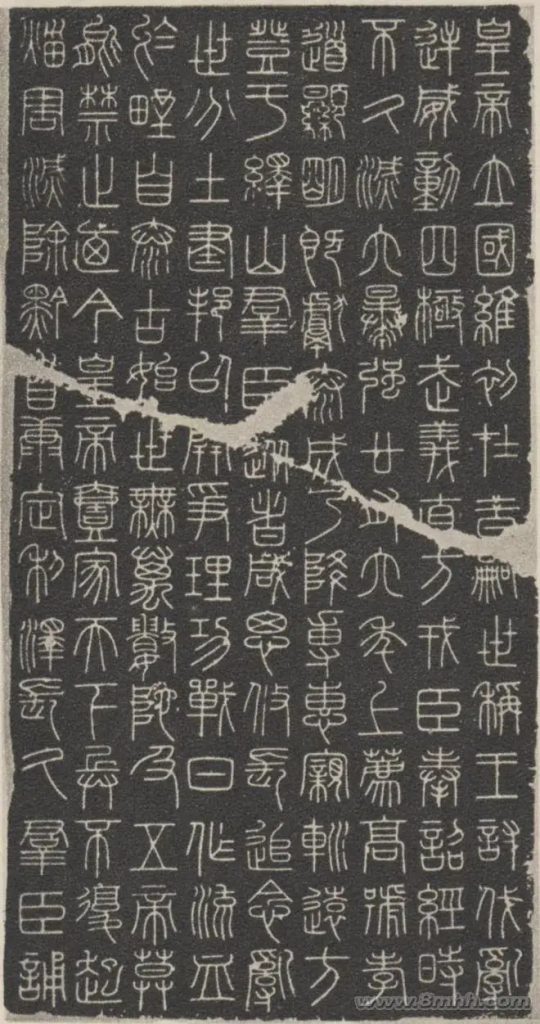

Qin Small Seal Script

Standardized under Li Si, Yi Ma Shan Stele exemplifies its elegant, flowing lines, signifying the final codification of Chinese characters.

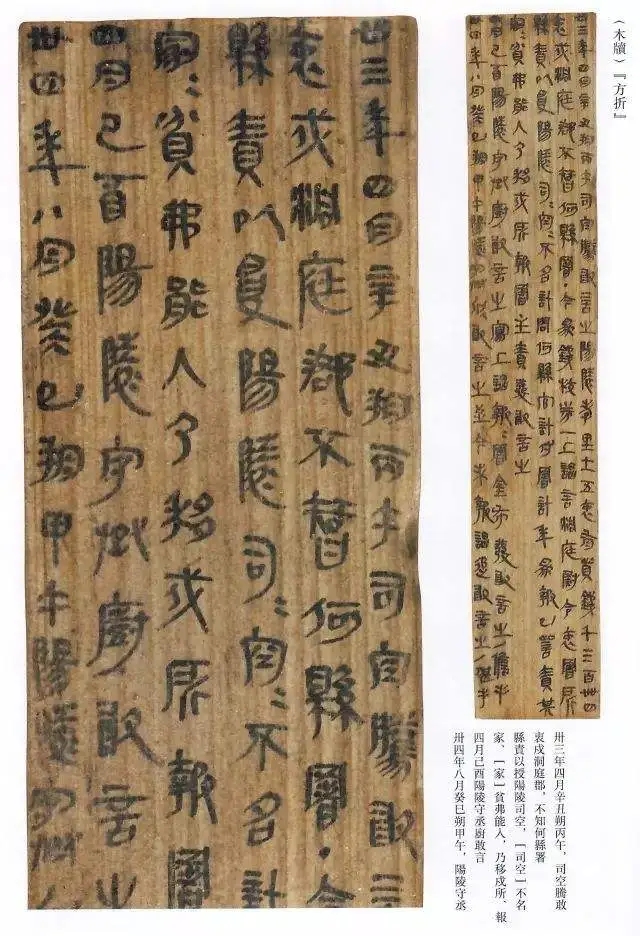

Han Clerical Script

By the Eastern Han, Cao Xie revolutionized script with “Eight-Division Style,” characterized by “goose-head” beginnings and “swallow-tail” endings (Cao Quan Stele). This radical break from seal script established foundational forms for later scripts.

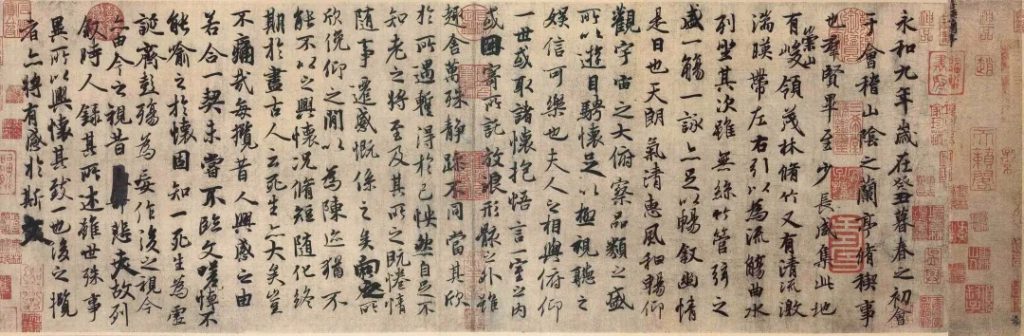

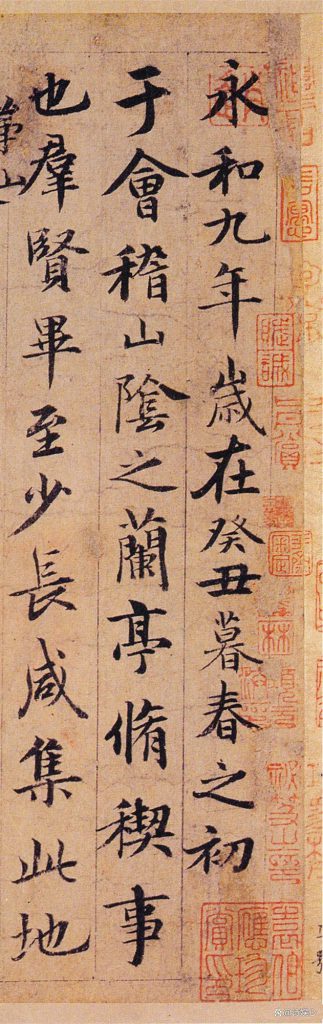

Wei-Jin Elegance

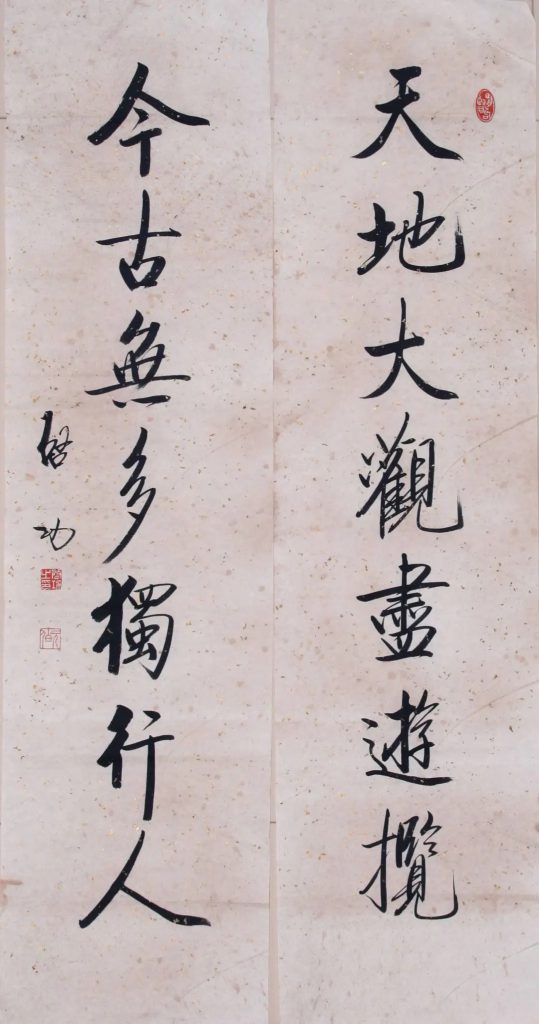

Zhong Yao’s Xuan Shi Biao set classical precedents for regular script, while Wang Xizhi’s Preface to the Orchid Pavilion achieved legendary status as the “Number One Running Script.” The era’s masters synthesized brushwork dynamism with Daoist principles of naturalness.

III. Flourishing Diversity (Sui-Tang Era)

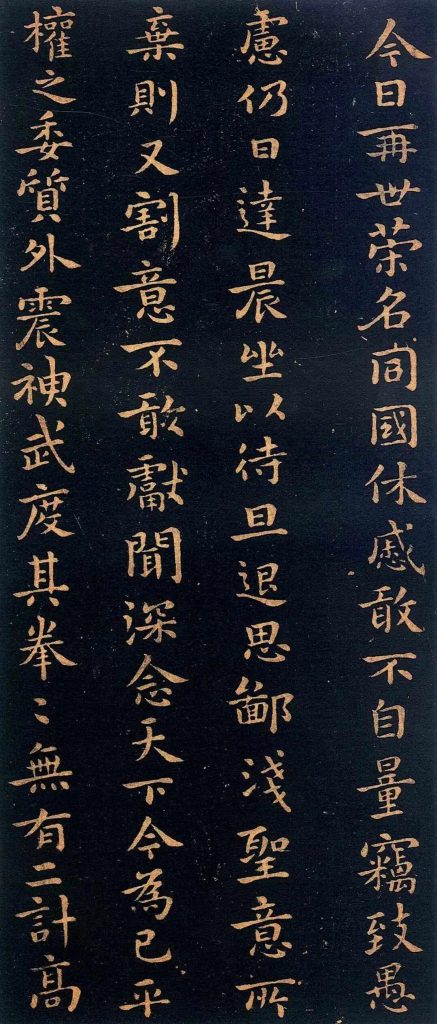

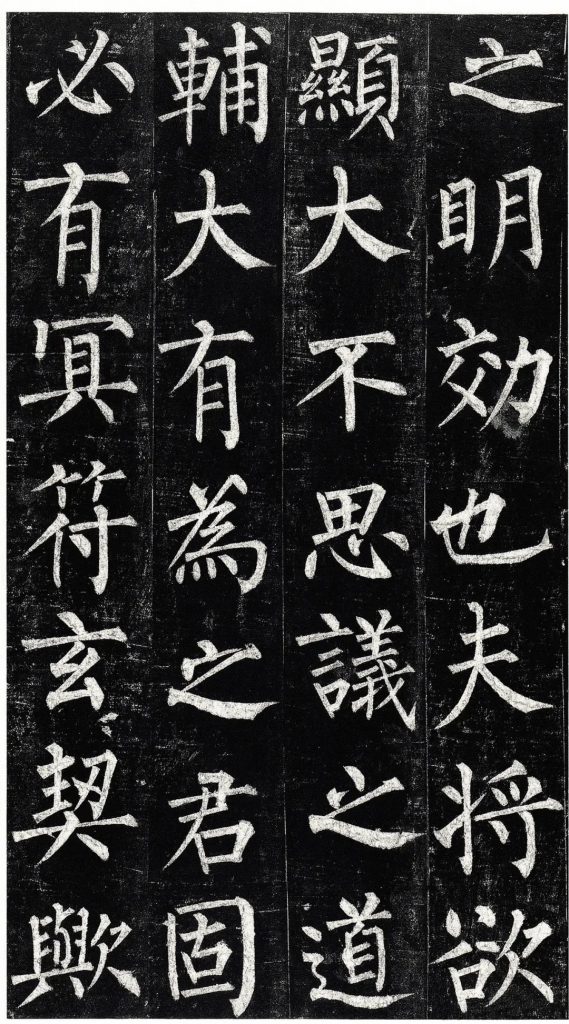

Tang Dynasty Regular Script

Ouyang Xun, Yan Zhenqing, and Liu Gongquan each developed distinct styles (Jiu Cheng Palace Stele, Memorial to My Nephew, Xuan Mi Tower Stele)—collectively forming the “Three Pillars of Tang Regular Script”—embodying strict formalism with personal expression.

Maturation of Calligraphic Theory

Sun Guoting’s Shu Pu articulated aesthetic principles like “divergence without violation, harmony without uniformity,” systematizing calligraphic philosophy.

IV. Literati Aesthetic (Song-Yuan Period)

Song Dynasty Neo-Confucianism in Calligraphy

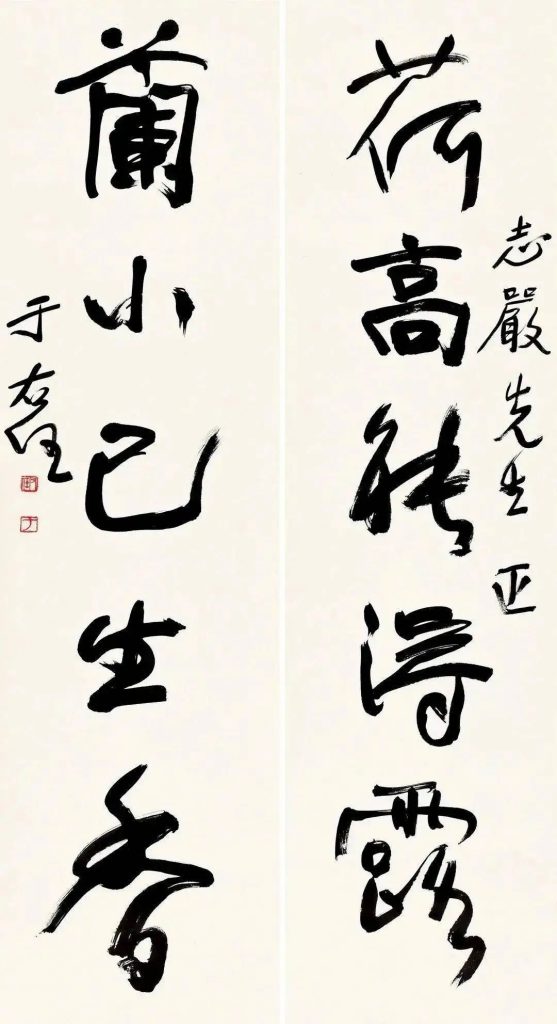

Su Shi’s “My Calligraphy Has No Fixed Method,” Mi Fu’s “Brush-Swiping Style,” and Huang Tingjian’s radiating compositions reflected literati ideals of integrating poetry, painting, and calligraphy.

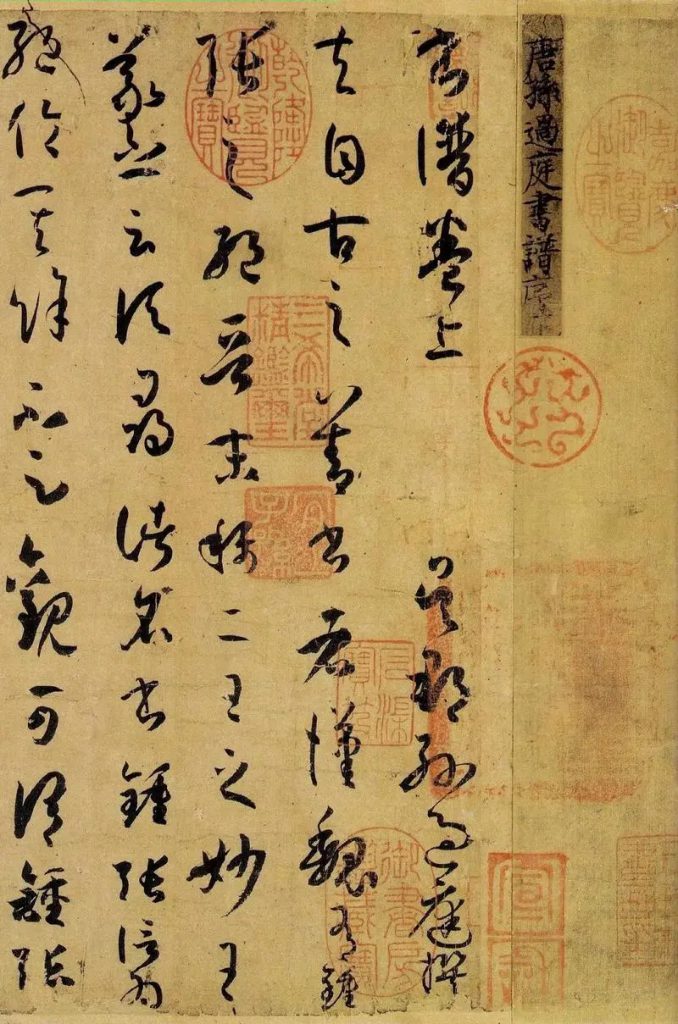

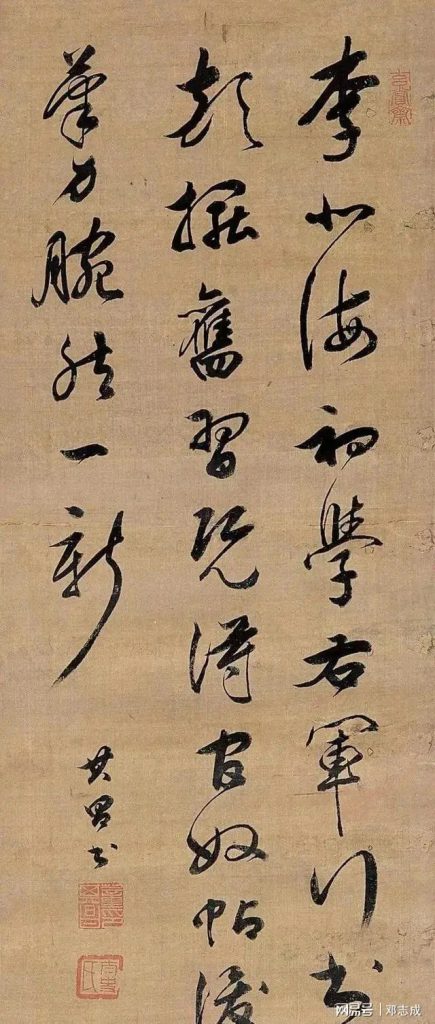

Yuan Dynasty Revivalism

Zhao Mengfu(revive antiquity with innovation), blending Tang Dynasty grandeur with Jin Dynasty refinement. His Postscript to the Orchid Pavilion became a canonical model for emulation.

V. Synthesis of Model and Seal Scripts (Ming-Qing to Modernity)

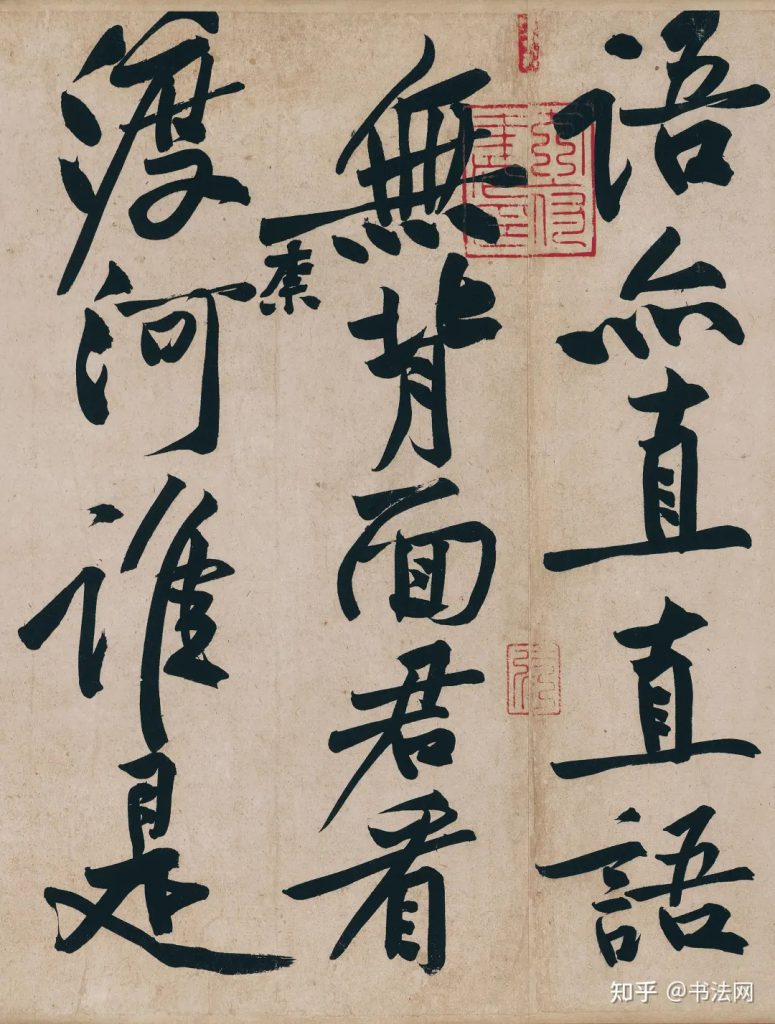

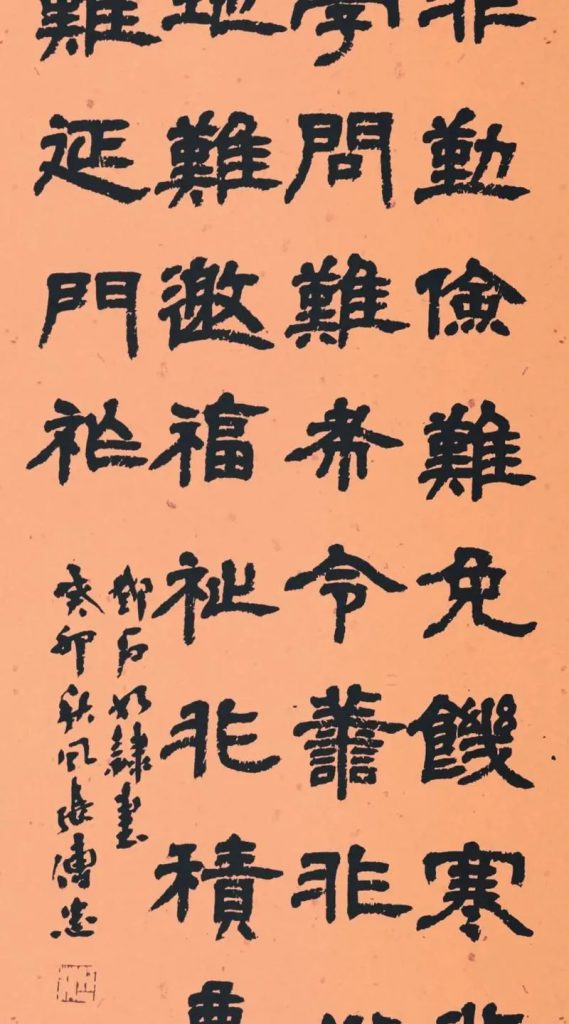

Ming-Qing Evolution

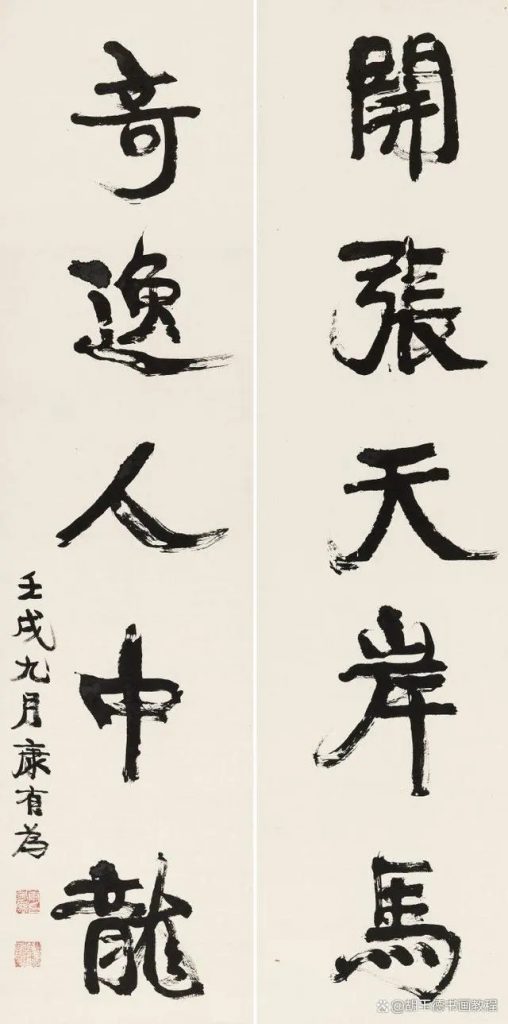

Dong Qichang’s “Southern-Northern School Theory” dominated discourse, while Xu Wei’s wild cursive style and Kang Youwei’s promotion of Wei stele aesthetics introduced new dynamism. Qing scholars like Fu Shan emphasized “Four Preferences/Abominations” (Si Ning Si Wu).

Inkstone Movement

Kang Youwei championed Northern Wei steles, while Deng Shiru fused seal and clerical scripts, creating robust, archaic styles that redefined artistic boundaries.

VI. Modern Transformations

The 20th century saw innovations like Yu Youren’s standardized cursive script and Qi Gong’s modern regular script. Digital technology has also enabled dynamic calligraphy and global dissemination through online platforms. Educational systems now systematically teach calligraphy, while international exhibitions and academic exchanges thrive.

Conclusion

Chinese calligraphy persists as a living art that bridges technique and transcendence (“technique perfected becomes Way”). From oracle bones to digital screens, it remains a visual manifestation of cultural identity and spiritual heritage, continuing to inspire awe and creativity worldwide.